What is this Constitution? It’s a collection of words. But words like these are never just words. Words have power; words are the inspiration to action. When Lokmanya Tilak declared “Swaraj is my birth right”, when Gandhiji called upon the British to “Quit India”, these were not just any words. They were words that set off a chain of actions that on 14th August 1947 culminated in Jawaharlal Nehru proclaiming to the world, “At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to light and freedom”.

Similarly, the opening words of the constitution contained in the Preamble are not just words. They are words that encapsulate the idea of the India that we have chosen for ourselves, the unshackled India that we want.

They are words that every Indian citizen should know by heart – and act to preserve, protect and defend. Our constitution is the product of 2 years, 11 months and 18 days of hard and selfless work by the Constituent Assembly. Not a single word of that constitution was written lightly. It was the product of expertise, deep thought, collaboration and spirited debate and discussion.

To paraphrase John F Kennedy’s remarks at a White House dinner honouring Nobel laureates, our Constituent Assembly was probably the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge that has ever been gathered together in India. The working of this Constituent Assembly is a shining example of the spirit that pervaded the birth of our nation. Seats in the Constituent Assembly were filled on the basis of expertise and diversity rather than party affiliations.

There were representatives from all parties including the All India Women’s Conference, the Hindu Mahasabha, the Communist Party of India Scheduled Castes Federation. Congress followed Gandhiji’s advice and selected distinguished persons outside the party irrespective of their political affiliations. Out of the trio affectionately dubbed The Three Musketeers of the Drafting Committee, – Alladi Krishnaswamy Iyer, KM Munshi and Gopalaswamy Iyengar – only Munshi was a member of the Congress.

The D’Artagnan to these ‘Three Musketeers’, was Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, a self-proclaimed “lifelong opponent of the Congress Party”. It was the spirit of collaboration among people like these, who found ways to work together for a common vision, that produced the Indian Constitution. It’s a spirit we would do well to cherish and emulate. The other interesting thing about the luminaries of the Constituent Assembly is their outward looking spirit. Almost all of these men were giants in their own field.

Indeed, after meeting Sir Benegal Rau who was on the Core Committee that drafted the Constitution, Justice Felix Frankfurter of the USA was so impressed with his abilities that he said he would have no hesitation in nominating Mr Rau to the Supreme Court of the United States.

But despite their eminence, the founders had the humility to study other constitutions, to consult the best minds of the day, to look for ideas wherever they originated and to discuss and respect opposing points of view. The concept of ‘Parliamentary democracy’ came from the British constitution, the ‘fundamental rights’ idea came from the US constitution, ‘liberty, equality, fraternity’ came ofcourse from France.

The constitutions of Ireland, Japan,South Africa, Australia and Canada and others contributed concepts and ideas. But (it) was no “bag of borrowings” as some critics called it. Each idea was put into an Indian context, discussed thread bare and then accepted, rejected or modified through a process of intense debate. That is the way to bring about transformational change.

Perhaps the single most radical decision taken 70 years ago, was the adoption of universal adult suffrage. India had no tradition of democracy. Literacy was a dismal 12 percent. At a rough estimate 80% of India’s population lived in poverty in 1947. And the majority of the population lived in far flung and often remote villages. In these circumstances, opting for adult suffrage was not just a risk – it called for a leap of faith.

Even in the West, the right to vote had come in dribs and drabs, expanding as conditions turned favourable. But our founding fathers chose not to wait for favourable conditions to emerge. Like Emmanuel Kant they believed that freedom precedes political maturity, and not the other way around. In fact, Madhav Khosla argues that India’s founders saw democratisation itself as a form of education, a way to responsible politics.

India’s voters have, in election after election, justified the founders’ faith. The individual also takes centre stage in the chapter on Fundamental Rights. For the first time in India’s history a declaration of the inalienable rights of an individual that could be enforced against the State, was articulated and given place of pride. The concept is based on the belief that there are certain basic human rights that no government, even a democratically elected one, can take away. Not surprisingly, some of these rights conflicted with other objectives of a free India. For example, the guarantee of Equal Protection under Law fell foul of the social agenda of acquiring zamindari properties without payment of full compensation.

The response of the government of the day, and most subsequent governments has been to bring in exceptions to the Fundamental Rights or to create vehicles like the Ninth Schedule which protects certain laws from judicial review, even if they violate Fundamental Rights. This is sometimes criticised as eroding Fundamental Rights by dilution. However, this tension between flexibility and permanence is a part of the dance of democracy. The founders intended the Constitution to be flexible to meet changing needs.

At the same time, judicial interpretation has held that the right of Parliament to amend does not extend to the right to change the basic structure of the Constitution. As long as that view holds, our Fundamental rights remain safeguarded. That being said, eternal vigilance is indeed the price of liberty and informed public debate is a must. It is disturbing for example to realise that whereas the Ninth Schedule originally housed only 13 laws enabling land reform, it now protects 282 extraconstitutional laws enabling nationalization, currency controls, price controls, and even the excesses of the Emergency.

Today, we also have a list of Fundamental Duties of citizens, which is as it should be. In my view, an important duty that is missing from the list is the duty of citizens to ensure by all peaceful means, that our great Constitution is followed in spirit as well as in letter. Nowhere is that spirit better captured than in the Preamble of the Constitution that we, the citizens of India chose to give unto ourselves.

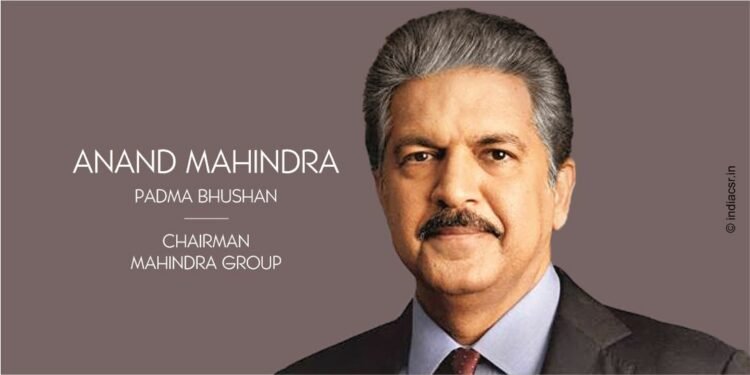

Anand Mahindra, a Padma Bhushan awardee, is a businessman and the Chairman of Mahindra Group, a Mumbai-based business conglomerate.

(Source: 70 Years of Indian Constitution, Published by Govt. of India)