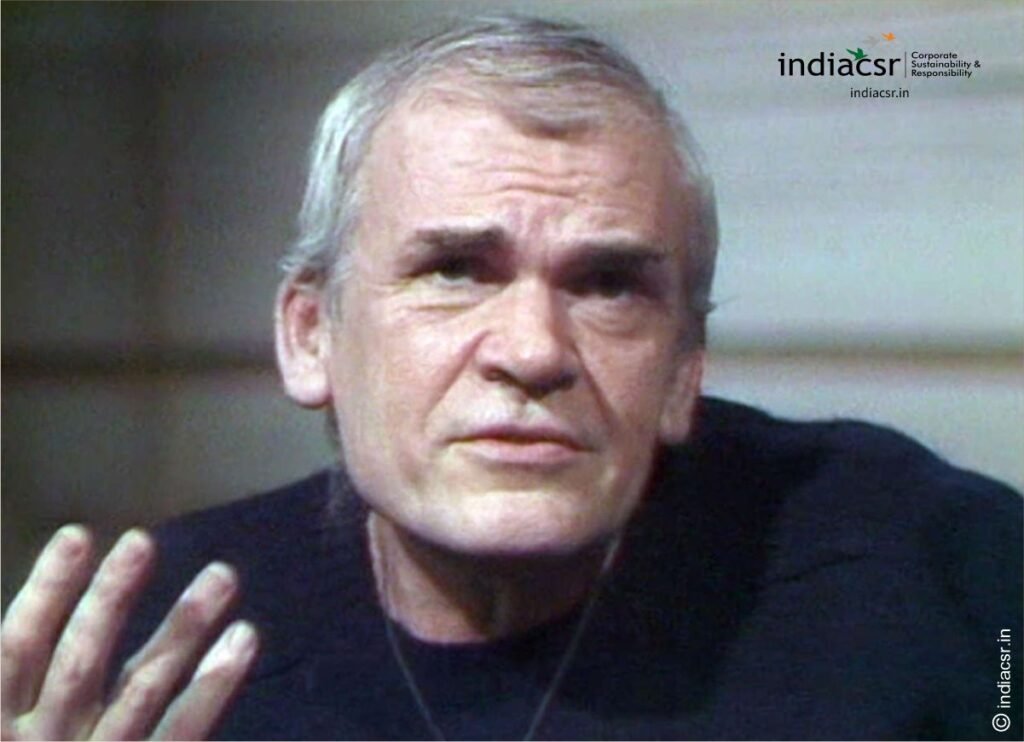

Milan Kundera, revered as the literary world’s anti-communism icon during the 1980s, was often misunderstood due to his association with the fall of the Soviet Union. Rather than a mere political commentator, Kundera was a profound artist, a master-jester against authoritarianism, creating lyrical and ironic works that delved deeper into the human condition beyond the confines of Cold War politics.

The Literary Dissenter

Kundera found himself in the company of esteemed dissident writers such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Joseph Brodsky, and Vaclav Havel, all being celebrated in both the West and democratic East. They were the vanguard against the ‘closed societies’ of the Soviet Empire, their novels illuminating the last chapters of the Cold War. Such was Kundera’s fame that a Literature Nobel seemed inevitable.

However, with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the subsequent implosion of the Soviet Union, Kundera, the author of ‘The Book of Laughter and Forgetting,’ ironically faded into obscurity as the ideological battle he had seemingly represented was considered over. Beyond Cold War Politics.

Kundera’s artistic prowess extended far beyond the role of a political dissident, which he had involuntarily come to symbolize. His work, imbued with a perfect blend of irony and lyricism—echoes of Cervantes, Rabelais, and Kafka—would be undermined if solely viewed through the lens of Cold War politics. Kundera was a comic writer in the purest sense, humorously highlighting the absurdities of ‘herd instinct’ and hero worship from both conservative and radical perspectives.

In ‘The Art of the Novel,’ Kundera dissected the concept of ‘comic,’ stating that while tragedy consoles us with the illusion of human greatness, the comic brutally exposes the meaningless of everything. Thus, Kundera’s work is a testament to the individual’s struggle against various forms of power, reminding readers that the “struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.”

Exile, Censorship and The Joke

Forced into exile in Paris in 1975, Kundera became a French citizen a decade later. Until the Velvet Revolution in 1989, which marked the peaceful shift from communist to democratic leadership in Prague, Kundera’s works were banned in his homeland. His debut novel, ‘The Joke’ (1967), is a satirical critique of communist totalitarianism, reflecting his belief that power structures dread mockery more than any other form of dissent.

The Enemy of Humourlessness and Kitsch

Kundera’s critique was not only reserved for humourless authoritarian figures but also extended to kitsch. He identified the ‘kitsch attitude’—which commodifies everything and intensifies frivolity—as a reflection of our need to be moved by our own beautified lies. In Kundera’s eyes, authoritarianism is the ultimate performance of kitsch.

Kundera’s Global Influence and The Forgotten Legacy

Kundera’s influence extended to the developing world, often referred to as the ‘global south’, trapped between the enthralling forces of capitalism and the paternalistic forces of anti-capitalism. He created an imaginative space for individuals desperate to avoid conforming to the herd mentality. In the binary, polarised world of today, it is unfortunately fitting that Kundera’s nuanced voice has fallen out of fashion, his memory faded.

In a world where laughter, joke, and comic are not just weapons but also poetic acts, Kundera’s voice of irony seems a forgotten echo. He passed away in an era blind to irony, unable to recognize its potency even when it greets you with familiarity. His life and work encapsulate an irony that sadly predates his death, reflecting a society too consumed in its own seriousness to appreciate the playfulness of his critique.