This article delves into the NZBA’s turbulent journey, the cascade of high-profile exits, the implications for climate risk management, and the uncertain path ahead for global finance in the face of a heating planet.

EU-based banks have not exited, perhaps because the EU aims to be climate neutral by 2050, a legally binding target enshrined in the European Climate Law.

In a world grappling with escalating climate crises, the financial sector’s role in steering humanity toward a sustainable future has never been more critical. Yet, as of September 2025, a stark reversal is underway. The Net-Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA), a United Nations-backed initiative launched in April 2021 to align global banking portfolios with net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, is unraveling under intense political scrutiny. On August 27, 2025, the alliance announced a pivotal shift: a member vote to transition from a membership-based group to a mere framework for guidance, effectively diluting its collective power. This move, prompted by member feedback, signals not just a tactical retreat but a broader weakening of net-zero commitments worldwide.

The political landscape has shifted dramatically, particularly in the United States, where the new administration’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement and halt on renewable energy investments have amplified geopolitical tensions. These changes have cascaded into the banking world, forcing institutions to weigh fiduciary duties against environmental pledges. As Christian Aufsatz, Managing Director at Morningstar DBRS’s European Structured Finance Ratings, notes, “In a world that continues to warm, banks’ capabilities to quantify climate risk are increasingly key to addressing the challenges posed by the severity of extreme weather events and their increased frequency.”

The Genesis and Swift Unraveling of the NZBA

The NZBA emerged as a beacon of ambition in the spring of 2021, uniting over 130 banks representing more than 40% of global banking assets. Members voluntarily committed to aligning their lending and investment activities with pathways to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, in line with the Paris Agreement. The alliance fostered collaboration on disclosure standards, target-setting, and transition plans, aiming to redirect trillions in financing from fossil fuels toward renewables and sustainable infrastructure.

But 2025 marked a turning point. The year began with a shockwave from the U.S., where political pressures—fueled by anti-climate rhetoric and trade wars—prompted major banks to bail out. In January and February, titans like J.P. Morgan, Bank of America, Citigroup, Wells Fargo, and Goldman Sachs severed ties. These institutions, which had been early NZBA signatories, cited internal capabilities to meet net-zero goals independently, without the alliance’s external scrutiny.

The exodus spread northward in February, engulfing Canada’s “Big Six” banks: The Toronto-Dominion Bank, Bank of Montreal, The Bank of Nova Scotia, National Bank of Canada, Royal Bank of Canada, and Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce. By March, Japan’s megabanks—Mizuho Financial Group, Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group, and Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group—followed suit, bowing to domestic pressures amid a global reevaluation of climate pledges.

April brought a symbolic blow: The NZBA voted to abandon its strict 1.5-degree target, settling for “well below 2 degrees Celsius.” As detailed in Morningstar DBRS’s March 2025 report, Net Zero Banking Alliance Pledge Likely to Remain Ambitious Despite Departures, this adjustment acknowledged the political realities while preserving some ambition.

The summer intensified the hemorrhage. In July and August, HSBC Holdings plc—the largest European bank by market capitalization—exited, paving the way for Barclays PLC in the UK. Switzerland’s UBS Group AG joined the fray in early August, the latest major defector. These banks insisted their departures were pragmatic, not opportunistic, emphasizing bolstered in-house climate risk frameworks. “From a risk perspective,” departing members argued, “we have sufficiently strengthened our capabilities to achieve net-zero GHG emissions by 2050.”

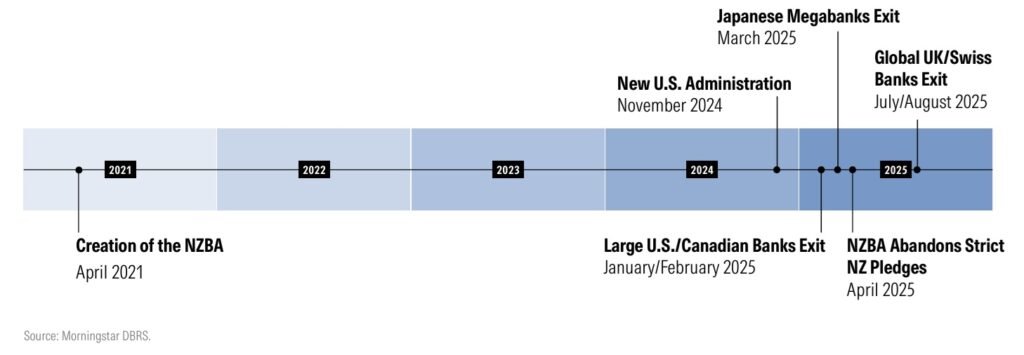

A timeline of these events, as illustrated in Morningstar DBRS’s Exhibit 1, paints a sobering picture:

| Year | Key Event |

|---|---|

| April 2021 | Creation of the NZBA |

| November 2024 | New U.S. Administration Takes Office |

| January/February 2025 | Large U.S./Canadian Banks Exit |

| March 2025 | Japanese Megabanks Exit |

| April 2025 | NZBA Abandons Strict 1.5°C Pledges |

| July/August 2025 | Global UK/Swiss Banks Exit |

This chronology underscores how swiftly political winds can erode collaborative efforts. The NZBA’s transformation into a non-binding framework, announced in late August, further erodes its influence, shifting from enforceable peer pressure to optional best-practice sharing.

***

Why the Exits? A Perfect Storm of Politics and Pragmatism

At the heart of this retreat lies unrelenting political pressure, much of it originating from the U.S. The administration’s Paris Agreement exit and renewable energy funding cuts exemplify a broader backlash against perceived “woke capitalism.” Geopolitical frictions—trade disputes, energy security concerns—have intertwined with climate skepticism, making net-zero alliances a lightning rod for criticism.

For banks, the calculus is clear: In jurisdictions hostile to green mandates, membership risks regulatory backlash or shareholder revolts. U.S. and Canadian banks, operating in fossil-fuel-heavy economies, faced lawsuits and legislative threats alleging fiduciary breaches for prioritizing climate over profits. Japanese banks, navigating a resource-import-dependent economy, similarly prioritized national energy strategies.

Contrast this with the European Union, where no major banks have defected. The EU’s legally binding 2050 climate neutrality target, enshrined in the European Climate Law, provides a sturdy backstop. The European Central Bank (ECB) exerts rigorous oversight, mandating disclosures on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) risks via Basel III Pillar 3 templates. As Vitaline Yeterian, Senior Vice President and Sector Lead at Morningstar DBRS’s European Financial Institution Ratings, observes, “EU-based banks are required to disclose qualitative and quantitative information on their exposures to ESG risks, in particular climate change risks.”

This regulatory armor has fostered resilience. Over 90% of EU banks now deem themselves materially exposed to climate risks—up from 50% in 2021—and all have integrated climate scenarios into stress testing. Yet, challenges persist: Mortgage portfolios, a cornerstone of EU balance sheets, often lag in risk integration, and quantification remains elusive for operational and market risks.

***

Climate Risks Amplify the Stakes: From Delays to Costly Realities

As banks recalibrate, the planet warms unabated. Morningstar DBRS’s July 2025 commentary, Climate and Credit: Short-Term Headwinds, Long-Term Risks, warns of a “business-as-usual” trajectory. Under Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)—even if fully implemented—global temperatures could rise 2.5 to 3.0 degrees Celsius by 2100, far exceeding Paris goals. Current Policies paint an even hotter “hothouse world.”

Physical risks are accelerating faster than models predicted. Extreme weather—wildfires, floods, heatwaves—strikes with greater frequency and ferocity, as seen in 2025’s Los Angeles wildfires and Southern European blazes. These events disrupt revenues, productivity, and supply chains, with insured losses hitting records. For banks, unmitigated exposures in sensitive sectors like tourism and real estate could cascade into defaults.

Transition risks, though somewhat diminished by delayed clean energy shifts, loom larger. Stranded fossil assets and abrupt policy reversals could demand “more dramatic and more expensive efforts,” per ECB analyses. Legal and regulatory uncertainties add volatility, as seen in evolving disclosure rules.

Net-zero goals demand massive investments: renewables, resilient infrastructure, green tech. Pioneers like the Netherlands exemplify integration—flood defenses alongside green housing—but many nations lag, hampered by politics or inertia. The NZBA’s dilution exacerbates this: Without membership’s collective push, global action fragments, delaying transitions and inflating adaptation costs.

Banks’ risk quantification is pivotal. Morningstar DBRS emphasizes that while awareness has surged, concrete modeling—especially for physical perils—remains nascent. EU banks lead in credit risk coverage but falter elsewhere. As Marcos Alvarez, Managing Director of Global Financial Institution Ratings, puts it, “We expect this to be the case for other banks outside of the ECB’s scope, too.”

A October 2024 Pillar III analysis revealed varied materiality: Some EU banks flagged significant portfolio sensitivities to acute/chronic risks absent mitigants, while most did not. Sector-level assessments highlight tourism’s vulnerability, with climate shocks eroding operating costs and revenues.

***

Looking Ahead: Uncertainty, Adaptation, and Persistent Pressures

The NZBA’s pivot to a framework initiative offers flexibility for banks in divergent regulatory landscapes but sacrifices scale. Best practices may persist—shared resources on disclosures and scenarios—but without binding commitments, momentum wanes. External variables—policy whims, tech breakthroughs, societal shifts—inject profound uncertainty.

Yet, glimmers of progress endure. Banks’ climate savvy has deepened; ECB oversight has mainstreamed risks into governance. Morningstar DBRS will continue embedding these into credit ratings, reflecting rising materiality.

Related research underscores urgency: Global Reinsurers H1 2025 (August 26) notes solid results amid catastrophe spikes; Wildfires in Southern Europe (August 18) highlights secondary perils’ insurance toll; Navigating a New Normal (June 10) warns Canadian insurers of wildfire volatility.

In Major Global Banks are Leaving the Net-Zero Banking Alliance: Does It Matter? (February 11), Morningstar DBRS pondered the exits’ weight—now, with the alliance’s reconfiguration, the answer leans toward “yes.” Political pressure has materialized, weakening global resolve. But as extreme events mount, banks must fortify risk tools, lest short-term pragmatism yields long-term peril.

The onus shifts to regulators, innovators, and society. In a 3-degree world, finance’s pivot isn’t optional—it’s existential. As Aufsatz, Yeterian, and Alvarez conclude, delays today compound costs tomorrow. The NZBA’s story is a cautionary tale: Ambition bends, but climate doesn’t wait.

The author is an editor at India CSR.

(India CSR)